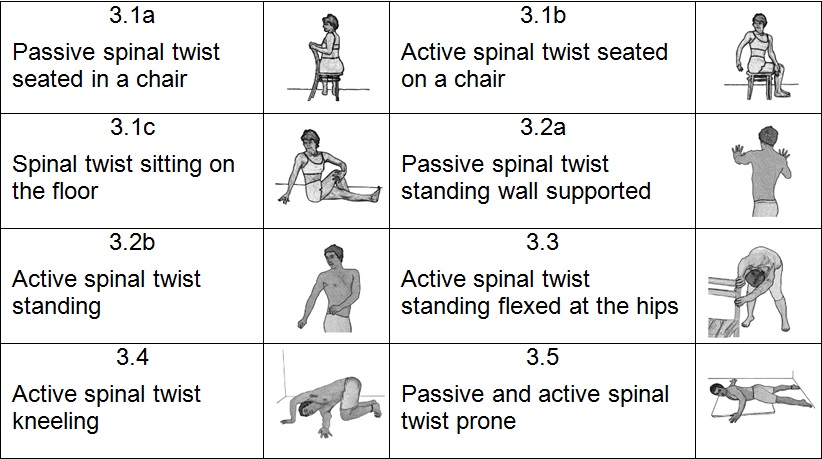

3.1 Spinal twist sitting – active and passive rotation stretches for the shoulders and the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine

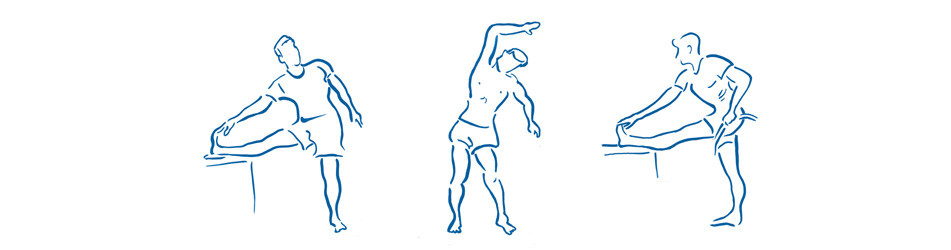

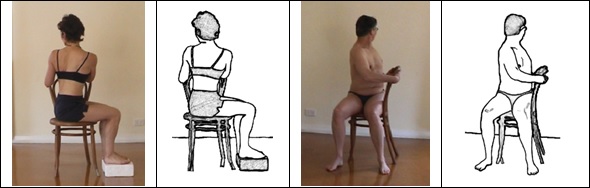

3.1a Passive spinal twist seated

Starting position

- Sit on a chair with your body at right angles to the back of the chair so the left side of your pelvis and thigh are in contact with the back of the chair.

- The seat should be horizontal so that you can keep a straight spine and it should be at a suitable height off the ground so that the soles of your feet are flat on the floor – alternatively place your feet on two blocks or books.

- Rotate your head, neck, shoulders and spine to the left so that you face the back of the chair.

- Grasp the back of the chair with both hands.

Technique

- Take a deep breath in.

- Exhale and rotate further left, towards the back of the chair by pulling on the back of the chair with your right hand and pushing with your left hand.

- Maintain rotation as you inhale and increase rotation with each exhalation.

- Passive rotation of the spine is produced using upper limb muscle contraction and leverage through the shoulder to the spine.

- Repeat the stretch by passively rotating the spine to the right.

Part B. 3.1 – 3.5 Spinal twist sitting, standing, kneeling and prone – active and passive rotation stretches for the shoulders and the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine

3.1a Passive spinal twist seated

Starting position

Starting position: Seated with your back straight and your body at right angles to the back of the chair, so the side of one thigh is in contact with the back of the chair. Ensure both feet are planted on the floor or blocks so your body is grounded and spine upright. Rotate your head, neck, shoulders and spine towards the back of the chair, and grasp it with both hands.

Technique: See Part A.

3.1b Active spinal twist seated

Starting position: Seated with your back straight and your body at right angles to the back of the chair, with the side of your thigh resting against the back of the chair. Ensure both feet are planted on the floor or blocks, and your spine is upright. Rotate your head, neck, shoulders and spine towards the front of the chair. Place the wrist of the hand nearest to your knee, against the side of your thigh and fully extend your forearm at the elbow. Allow your other arm to hang freely from the shoulder down at your side.

Technique: See Part A.

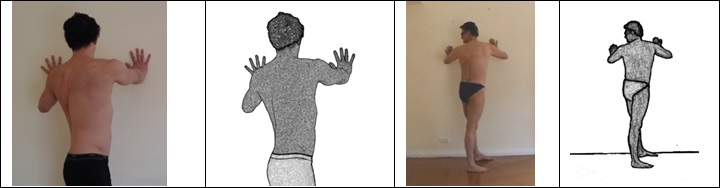

3.2a Passive spinal twist standing wall supported

Starting position: Standing with your feet apart and the left side of your body about 20 cm from a wall. Flex your forearms about 90 degrees and flex your arms 45 degrees. Rotate your head, shoulders and spine to the left, so that your upper body faces the wall, but keep your pelvis fixed. Place your palms flat against a wall or intermesh your fingers in a wire fence about shoulder height.

Technique: See Part A.

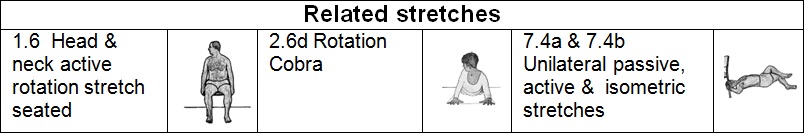

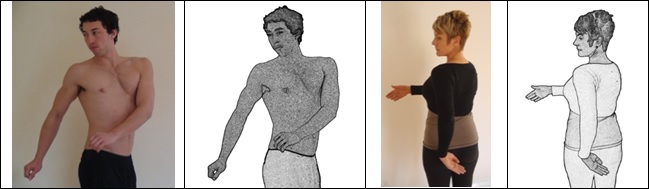

3.2b Active spinal twist standing

Starting position: Standing with your feet apart and your arms at your sides. Rotate your head, neck, shoulders and spine to the left but keep your pelvis and lower limbs in a fixed position. Relax your shoulders so they are dropped and your arms hang freely at your sides.

Technique: See Part A.

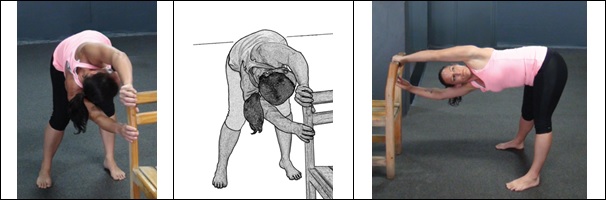

3.3 Active spinal twist standing flexed at the hips

Starting position: Standing with your feet 30 to 50 cm apart, about 1 m from a chair or table. Flex about 90 degrees at the hips and grasp the back of the chair. Lean backwards, away from the chair and drop your upper thoracic spine towards the floor. Keep your spine, legs and arms straight. Rotate your spine to the left, so that your upper body faces sideways. As an alternative to using a chair for support grasp a wire fence.

Technique: See Part A.

3.4 Active spinal twist kneeling

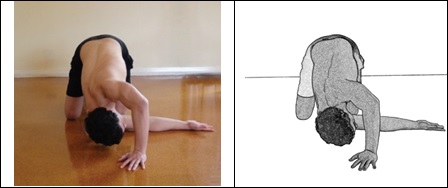

Starting position: Kneeling with your hands palms down on the floor in front of you – as in the cat position. Move your left hand a few centimetres forward and flex your left elbow. Lift your right hand off the floor, then slide it along the floor and under your body to the left. This will rotate your spine to the left. The back of your right hand and arm rests on the floor, and your left elbow is flexed about 90 degrees.

Technique: See Part A.

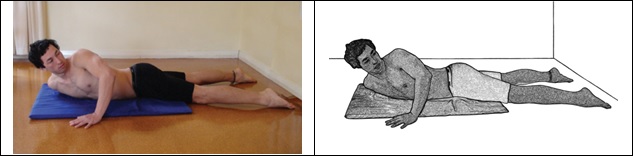

3.5 Passive and active spinal twist prone

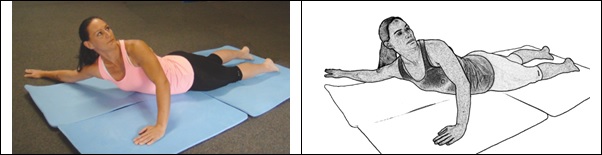

Starting position: Prone with your feet apart and your toes pointing backwards. Abduct your arms until your hands are level with your shoulders. Flex your left elbow and place your hand, palm down, nearer to your side. Raise your head and left shoulder and left elbow off the floor. This will rotate your spine to the left. Keep your pelvis on the floor.

Technique: See Part A.

Direction and range of movement

Total spinal rotation to one side is about 130 degrees. Rotation of the head and neck (Occiput to C7) is about 90 degrees; rotation of the thoracic (T1 to T12) is about 35 degrees; and rotation of the lumbar (L1 to Sacrum) is about 5 degrees.

During trunk rotation there is about 14 cm of medial to lateral movement of the scapula along the rib cage (10 cm abduction and 4 cm adduction). During rotation one scapula moves away from the spine and around the chest wall (protraction or abduction) while the other scapula moves towards the spine (retraction or adduction).

Most spinal rotation occurs in the cervical spine, mid thoracic spine and at the junction of the thoracic and lumbar spine.

The passive spinal twist standing wall supported and the active spinal twist standing 3.2b also involve internal hip rotation on one side and external hip rotation on the other side.

Target tissues

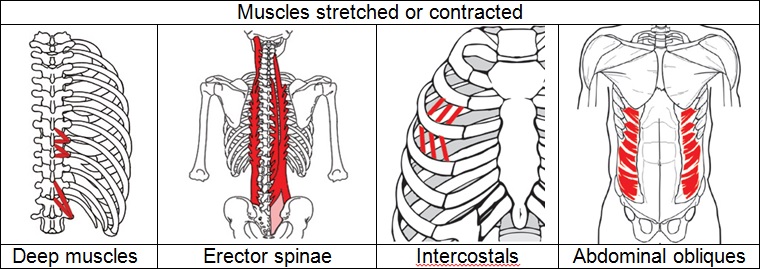

The spinal twist is primarily a stretch for the deep rotator muscles of the spine – the semispinalis thoracis, rotatores and multifidus. The lower origins of these muscles are anchored to a vertebra or rib by the weight of the body, while the upper ends attach to a vertebra or rib, one to six levels above.

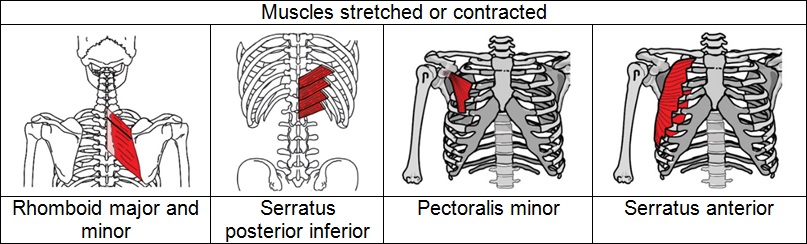

This is also a stretch for the middle trapezius, rhomboid major and minor, abdominal obliques, intercostal muscles, serratus posterior inferior, spinal ligaments and thoracolumbar fascia.

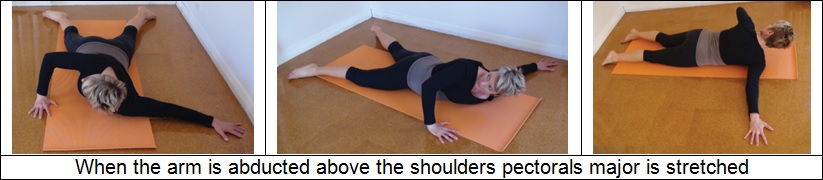

This is also a mild stretch for pectoralis minor and serratus anterior. If the arm is abducted above 90 degrees, for example during the spinal twist prone 3.5, then it becomes a good stretch for pectoralis major and its surrounding fascia.

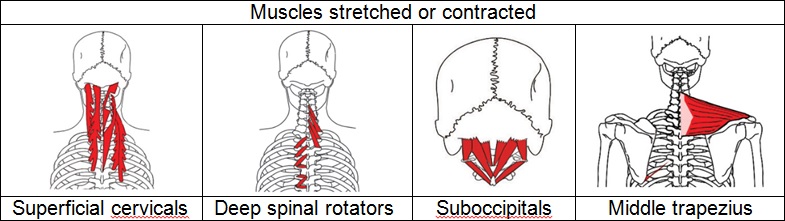

When the head is rotated this is also a stretch for the suboccipital muscles – mainly rectus capitis posterior major and obliquus capitis inferior; the deep cervical rotator muscles – multifidus; and the superficial posterior cervical muscles – semispinalis capitis, semispinalis cervicis, splenius cervicis and splenius capitis; and longissimus capitis and iliocostalis cervicis in the erector spinae group.

Greater rotation is achieved with the passive stretch, however more muscles are strengthened with the active stretch; these muscles being the antagonists to the muscles being stretched. They reside on the opposite side of the body and are the same by name as those listed above.

Other factors

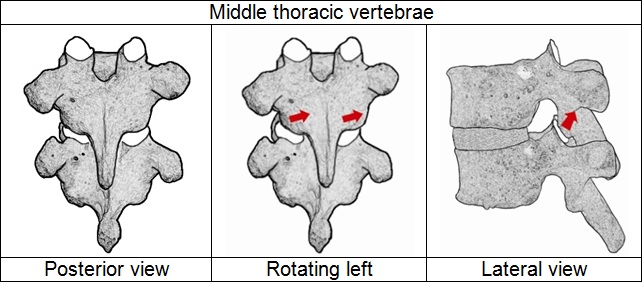

The range of rotation is not the same at each vertebral level throughout the spine. Rotation is coupled with flexion and sidebending towards the same side as rotation. There is greater rotation in the thoracic compared with the lumbar spine. The range of rotation increases as you descend the spine and peeks at T7. It decreases between T8 and T10 and peaks again at T12. Rotation decreases considerably in the lumbar region.

Although rotation is limited by the rib cage it is the freest of all movements in the thoracic spine. Rotation increases from T1 to T7 because the ribs increase in length and decrease in curvature and because of the plane and shape of the costotransverse joints.

Rotation is less between T7 to T10 because the ribs get shorter and more curved and because they are part of a more rigid structure, a ring of cartilage, bone, ligaments and joints, serving as an anchor for the diaphragm and abdominal muscles.

Ribs 11 and 12 give the thoracic greater flexibility because they are free at their anterior ends, and do not attach on costal cartilage or the sternum.

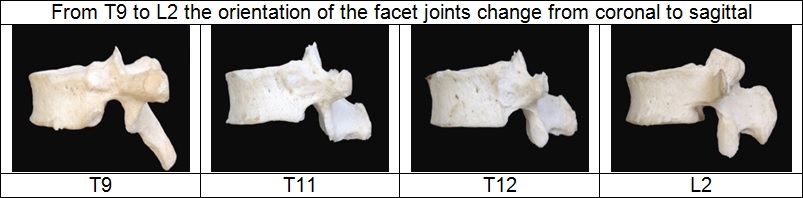

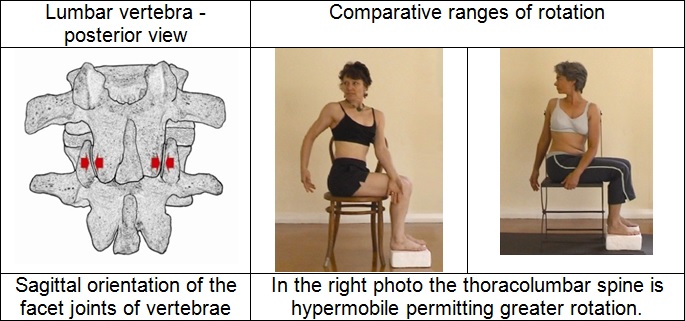

The range of rotation is determined by the shape and orientation of the facet joints. The sagittal orientation of the facet joints in the lumbar spine significantly limits the range of rotation to only one degree per vertebra. In contrast the coronal orientation of the thoracic facet joints permits three times as much rotation per vertebra.

The transition from a coronal orientation of the facet joints in the thoracic to a sagittal orientation of the facet joints in the lumbar is shown below. In the lumbar sacral spine (L5/S1) the orientation of the facet joints can vary from slightly sagittal to slightly coronal and may be asymmetrical. The range of rotation between individual will vary. Movement in the lumbar and sacral spine is also limited by strong iliolumbar ligaments.

Safety

The spinal twist seated in a chair is a relatively safe technique and carries few risks unless there is an underlying pathology or congenital deformity.

Avoid slouching during the rotation stretch. If the spine is kept in neutral – in other words neither in flexion or extension – then this will result in optimum rotation. This will maximise the overall range of rotation and the rotation will be distributed throughout the spine, appropriate to the anatomy of each vertebra.

Do not allow the pelvis tilt backward, the lumbar lordosis to flatten out or reverse, and do not allow the mid thoracic spine to flex or the thoracic kyphosis to become exaggerated.

This stretch should only be done sitting on the floor, if your hips joints are flexible enough and your hamstrings long enough to allow you to sit up straight, and maintain a comfortable upright position. People who have spent their whole lives sitting on chairs may not have sufficient flexibility to do the spinal twist while sitting on the floor and keep an erect spine.

Doing this stretch with a stooping posture restricts rotation, reduces it benefits and can cause injury. Until you have gained sufficient flexibility in your hips you should only do the chair technique. If you have healthy knee joints, another option is to do the active spinal twist kneeling.

Care should be taken not to over stretch the thoracolumbar part of the spine. If the area is hypermobile further stretching may result in increased hypermobility, ligament strain and injury.

Vulnerable areas

Key